Williams River Ecology

Edited talk given by Bill Dowling on 12 April 2008 at the Wise Ways to Water Forum at Wangat.

I’ve lived all my life at Bandon Grove on a property that extended from just above the junction of the Chichester and Williams Rivers to just below the proposed dam site at Tillegra. I have always had an avid interest in natural history in general and over the years have studied many aspects of it relating to the general Dungog area but in particular the area of the Upper Williams. Consultative work for NSW NPWS has resulted in internal publication of a number of scientific papers-these in particular have concentrated on the rare and threatened flora of the Barrington Tops National Park. I’ve participated in extensive studies of the family ORCHIDACEAE, the native orchids, for Dr David Jones and Dr Mark Clements of the Centre for Biodiversity Research at the CSIRO in Canberra. More recently I have just retired from 8 years as field supervisor/ecologist with NSW State Forests. Since retirement late last year I have been actively involved in a continuation of work that was first commenced through State Forests on what has been officially described as the most scientifically sensitive project ever undertaken in the history of the Roads and Traffic Authority in NSW-the bypass of Bulahdelah township by the Pacific highway. Perhaps Tillegra Dam is second!

I think we would all be aware, and all agree that a project such as is proposed for Tillegra Dam, its pre-construction phase (the period during construction and the period during filling and after filling and for many many years afterwards) will inevitably lead to massive changes to the ecology, and the biodiversity of the Williams River Valley, both upstream and downstream of the actual dam. Some of these changes can probably be predicted with a fair amount of accuracy but with others it may well be a waiting game.

My early records and recollections of the Williams River go back to the mid 1950s and I have certainly seen many changes to the river, its ecology and its general environmental appearance. These changes relate to both the fauna and flora components as well as its structure and appearance. Some changes have had a natural cause: differing weather patterns with resulting alteration to rainfall patterns; flood events both major and minor. Other changes are the result of either direct or indirect human activities: land clearing, weed invasion, changed farming practices to name just a few.

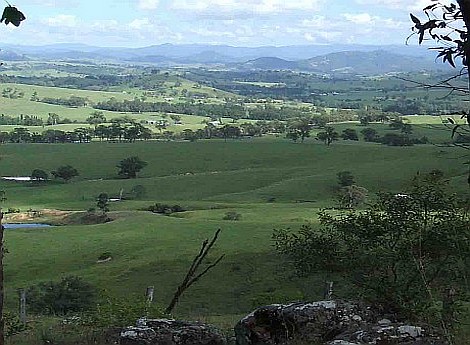

Most of today’s generation would not realise that so many of what are now hillsides covered in regrowth vegetation, were, only a matter of decades ago, cleared of most, if not all vegetation, this land clearing being the result of farmer’s actions.

I have seen the maps of the early surveyors dating back to 1830 when they first surveyed the Williams River along its entire course, and these maps have notes that indicate that most if not all of the hillsides in this Upper Williams Valley were at least thinly wooded all over but mostly they were thickly wooded with thick scrubby, brushy, rocky gullies.

There are many indicators of a healthy river system – one of these is fish: their diversity of species and the numbers of individuals within each species are two significant points. Dr Hugh Jones has indicated that in studies that have been conducted, mostly in the ’90s and continuing up to recent times, 17 species of fish have been recorded in the Williams River. These species include: eels, gudgeons, bass, mullet, gambusia, herring, smelt, galaxias, bullrout, carp and catfish. Most of these species are native to eastern Australia; Gambusia holbrooki is an introduced species; some are not native to the Williams River – carp is another introduced species that has been slowly making it’s way up the river system – at last reports that I’ve heard of it is just below Bandon Grove bridge, but it may be further upstream. The catfish is only a fairly recent arrival and certainly was not to be found in the river prior to the 1980s.

Of great interest and concern is the marked decline in numbers of fish individuals. An interesting historical newspaper article that I’ve seen talks about a small fishing party in the 1880s that caught over 80 bass in a two hour period at a spot just upstream from Munni House where Taylors Creek enters the main river (and all of these were a keepable size).

In the 1860s a blind Aboriginal woman named Tilley, was able to fulfil her role as a food gatherer for the tribe by catching an almost endless supply of bass from a favourite camp site on the riverbank on Canningalla station downstream from the dam site.

In my younger days during the 1950s and 60s it was a very easy task to catch a meal of fish for the family evening meal (much to the horror of my mother, who for some reason hated cooking fish). It was a recognised fact that bass could be caught during any month of the year that had an ‘r’ in it, so from September through to April were bass months – with May to August being unproductive – the colder winter water in the river and the fact that bass migrate downstream to brackish water to breed were both contributing factors to the lack of bass during winter.

Another species that used to be extremely common was the herring – these could be caught in large numbers with suitable gear, skill and lots of spare time.

And yet again the two species of mullet were present in large numbers during the summer months, autumn saw them also migrating downstream to the sea. Sometimes small groups of them remained in the river and these invariably suffered from the effects of the cold winter water and would become very sluggish and often partly blind and in this state would be easy pickings for the majestic sea eagles that would follow the river systems upstream, feeding on the mullet as they went. These birds normally nest in the coastal regions but for a number of years they had a nest beside the Chichester Dam lake. Two individuals are at the present time found in the area of the Chichester/Williams junction.

Releases of cold, lower level water from Chichester Dam at various times in the past has always resulted in reduced numbers of fish being present in the river between the dam and the junction with the Williams. Similar effects could be generated below the proposed Tillegra Dam.

The Williams/Chichester junction at Bandon Grove has in the past traditionally been known as an extremely deep, dangerous hole of water to be avoided for swimming purposes – there have been drownings there when people got into difficulties in the cold, deep water. This is not the case now, with the water being very much shallower than what it used to be.

Catfish are not a native to the Williams or in fact to the Hunter River system. They were not to be seen in the river prior to about the early 1980s. It is probable that they were introduced to the Lostock Dam on the Paterson river and have moved down that stream and up into the Willams.

Carp of course is also an exotic species and they have been present in the Hunter River at Maitland for quite a few years so it has only been a matter of time before they have migrated up into the Williams.

Probably the biggest cause of the collapse of the fish population in the Williams River was the construction of the Seaham Weir. It was only a relatively short period of time after the weir went in that fish numbers declined and they have never recovered despite the assurances of Hunter Water that suitable fish ladders had been incorporated in the weir to allow fish to proceed up stream. I believe that the original ladder was totally inadequate in its design and that the alterations made since have not really helped. These are my own personal observations and I may be wrong.

Another fascinating and very important component of the fauna of the Williams is the freshwater mussel. I myself have had an interest in these since the late 1950s and the 5 species that Hugh Jones has found in the river during recent studies were all present back in those earlier years. Hugh states in an article, ‘my work in the Hunter Valley has shown the Williams River to have a diverse and abundant mussel fauna’…‘no other stream, in the Hunter Valley, with the exception of the Paterson has all the 5 species’.

One mussel species, the quite large Cucumerunio novaehollandiae will be at most risk from dam construction – it requires highly stable bed sediments combined with strong stream flow, two elements that can’t be guaranteed during and after construction.

It is interesting that one of the sites where Hugh has found this species at the present time is exactly the same spot where I located it in 1958. I did some extensive collecting of live mussel specimens in 1958 for Dr Don McMichael, the curator of shells at the Australian Museum in Sydney. Don and Mr I.D Hiscock of the University of Queensland at the time were writing what was later published as ‘A monograph of the Freshwater Mussels (Mollusca: Pelecypoda) of the Australian Region’. Some of the material I collected also provided Don with examples for the first time, of the interesting very early larval stages of 2 species of mussel. It should be noted that freshwater mussels depend on a fish host to complete their life cycle. In their very early stages they attach themselves to the fish host, often around the gills, and here they stay for up to 12 months, before detaching and becoming free living individuals.

There is much visual evidence to show the changes in the river’s course that have occurred, sometimes in the distant past, and sometimes in much more recent times. In 1939 the stream below Canningalla homestead, for reasons I’m not aware of, started to change it’s course dramatically. My family could see the potential for losing many hectares of rich alluvial flats if nothing was done. Their pleas to the government for help either financially or in other ways fell on deaf ears, so they took it onto themselves to construct quite large wooden groins that diverted the water off the unstable river bank until remedial vegetation plantings could take hold. This worked extremely well for a number of years, until a later very large flood got in behind the works and washed most of it away. This was the start once again of extensive erosion that has led to the river now being close to 300m away from it’s original location, and the only thing that has stopped it going any further is a high, solid rock cliff face.

The 1950s were a very wet period with numerous rain events that resulted in many rises in the river flow, both minor and major. Much erosion took place during this period of the alluvial river flats. Much has been written about past efforts to tame and train the Williams River. In the 1950s much money and manpower was used to de-snag whole sections of the river. Any trees, logs, rocks either on the river bank or in the stream bed that were hindering or likely to hinder the water flow in the remotest fashion were removed completely! This was followed by construction of fences over areas that had been levelled out – these fences consisted of railway line for posts, sometimes very large steel cable for wires and steel mesh netting, and in the compartments formed by these fences were planted many 1000s of trees, mostly willows.

These activities took place, not only in areas of active erosion, where something needed to be done rather urgently, but also in other places that were quite stable with no erosion what-so-ever.

And then, lo and behold, another team came onto the scene and what were they doing? Placing logs back in the river and along the river banks!

Most of these activities had a devastating effect on the river, it’s wildlife – both fauna and flora, it’s diversity of wildlife in general. It is a great pity that we don’t have much baseline information from these earlier days, not only of the Williams River but also of the Chichester River both before and after the construction of the Chichester Dam.

It is extremely pleasing to see the amount of interest being generated and the studies that are being undertaken by researchers at this time even though it could be said that this is a very rushed process given the short notice we’ve been given by the government leading up to proposed start of dam construction, if it is allowed to go ahead.

Observations on the Williams River and the effect Tillegra Dam would have on the fauna, would not be complete without mentioning that iconic species, the PLATYPUS. These were once very common along extensive stretches of water from the junction upstream to the headwaters. Numbers have decreased over recent times and in particular since the remedial works undertaken on the river since the 1950s. These works caused destruction of habitat, changed water flows and altered other critical aspects of the river system that were essential for the long term viability of a sustainable population of these unique monotremes. Although still to be found by those that know how and where and at what time to look, the future for these amazing animals looks very bleak should Tillegra Dam be built, with existing habitat that will be under and in the pondage being unsuitable, and downstream populations being effected by changed water flows, flood flows and colder dam water, when it is released.

A final observation and query regarding two flora species…

(1) Why is it that the Weeping Bottlebrush Callistemon viminalis is only found along the Chichester River and along the Williams downstream from the junction and not upstream?

(2) And why does the Weeping Lilly Pilly tree (known locally as Ironwood), Syzygium floribundum (formally Waterhousea floribunda) only grow along the Williams and not up into the Chichester above the junction? One possible answer may be that the soils in the Chichester and Williams Valleys have been derived from the decomposition of basaltic parent rock that originated in different larva flows from the ancient Mt Barrington volcano (44-54 million years ago) and therefore these soils may have a different chemical makeup from each other?????