Farewell Journey

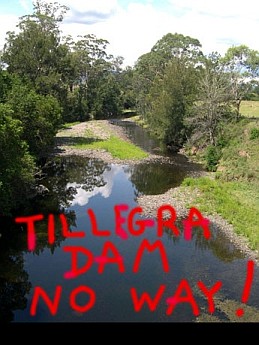

A river has a mind of its own. It is a living thing. We meddle with rivers at our own peril. The Williams River, north of the New South Wales town of Dungog, has seen less meddling than most. But the Tillegra Dam will change all that.

The dam is to be built as a supplement to the water supply for Newcastle and the Central Coast, to “drought-proof” the region for the next sixty years. But in the process a valley will be flooded, a valley that is presently home to farming families some of whom have been there for five generations.

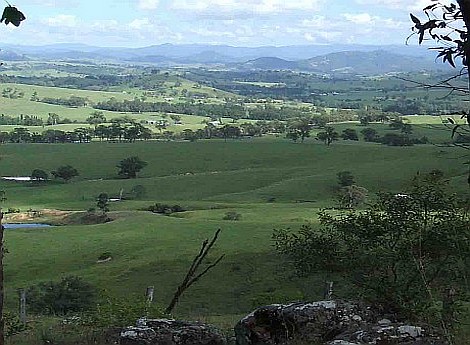

The outcry about the dam is with these farmers in mind, and the productivity of their land in a fertile and rain-rich region in the foothills of the Barrington Tops mountains. The clouds roll in from the sea and as the land rises the rain falls: so it has been for all our recorded history and a whole lot longer. There has been talk of damming the Williams River at Tillegra for at least half a century, and if the Hunter Water Corporation’s dam on the neighbouring Chichester River is anything to go by, this is good water-harvesting country. If only water was the only consideration.

As well as the farmland, it is the river itself that will be lost – twenty-two kilometres of meandering stream lined with river oaks and water gums. Deep pools home to platypus. Shallow rippling stretches where white-faced herons snatch a meal. Bends where campers set up in the summer and catch bass while kids frolic in the rapids and make their own little dams with the water-rounded stones.

The Gringai people would have had an easy time, walking up this river. They would have known, where the river almost loops back on itself, where to cut across to abbreviate their journey. They’d have known the deep pools and ways to approach them or circumvent them. They’d have known where the big floods run their own course and where the last pools hold out in drought.

All I had was a contour map, the knowledge of a few farms I’d visited over the years, and a warning to watch out for stinging nettles and electric fences. I figured that covering twenty-odd kilometres walking in the river wherever I could might take me three days. No short cuts. Only a retreat to the bank if the alternative was to swim. If the river was going to drown I was going to pay it the respect of the closest attention I could possibly grant it. I would write about my impressions. I would carry a tripod and carefully photograph this river in all its moods. I would travel at the time of a full moon, and sleep in a hammock strung close to the water’s edge.

I ‘phoned a few of the farmers I knew to advise them a vagabond would be travelling through their territory. Technically their land stops at the river’s edge and I was in a sort of terra nullius, the Gringai river that nowadays seems to be owned by the Hunter Water Corporation and the Hunter-Central-Rivers Catchment Management Trust rather than mere farmers and campers and fisherfolk and river wanderers….

Could I drink the water? After all, Hunter Water pumps out of this river downstream at the Seaham Weir and sends it over to Grahamstown Reservoir for Newcastle’s water supply – and some for the Central Coast too. Yes it does go through a water treatment plant. But when I set off from the Tillegra Bridge that was my first impression: this is a really clean river.

My second impression wasn’t so cheerful. The catchment management people have been leaning heavily on these farmers because their cattle go down to the river to drink. So the farmers have been co-operative and fenced their river flats to leave a cattle-free strip along the river. Sounds good? Wrong. The river banks in the ten kilometres or so above the Tillegra Bridge are a haven for the most astonishing diversity of weeds I have ever seen. Thistles, wandering jew, privet, stinging nettles, bamboo, willows, and I swear another score or two of species for which I had familiarity but no name, or were weeds completely new to me. There were even weeds that climbed to the upper branches of the river oaks. Meddling? This was like a massacre.

But the water was fine. The birds told me that: azure kingfishers, heron, ibis, a cormorant, and wood ducks aplenty. The first night, after carefully trampling the nettles I strung my hammock, boiled the billy and watched the moon rise over the Chichester Range. Leseuers tree frogs and leaf-green tree frogs called. At dawn, with mist a light blanket over a deep pool, I watched a pair of platypus surfacing for air, diving, surfacing for air. A clear river and a healthy river.

Then more meddling. Those catchment management experts again. Steel girders driven into the river bank on the outside of a bend and chain-link wire strung between them. Taming the wild thing. Stopping those floods eating away at the rock and the soil. God-playing. Now the rusty tangle of wire mocks them and pocks the river like graffiti. They might as well have dumped old car bodies there. It’s a mess and it didn’t work and I make a note to write and ask that the vandalism be removed.

But there’s an easy solution to the steelworks and the weeds: flood the lot. Obliterate all that whitefella pomposity and make a nice lake. Soften up the protest by promising watersports and picnic areas and a newly planted forest all around the shore.

But a reservoir doesn’t have a fixed shoreline. Like a farmer’s tank, the water rises and falls dramatically with the seasons. Most of the time the Chichester Dam is less than full, and because it is sited in steep country the rises and alls don’t vastly change the shape of the surface. The Tillegra Dam is so very different. A ten metre drop in the water level will in many places leave a beach like low tide at Broome. So much of the reservoir floods relatively flat country. Where do you put the picnic tables and the boat ramps? And when that shallow water warms up, how much is evaporating from the full reservoir on a summer’s day?

My second night’s camp was beside the biggest water gum I have ever seen, with six trunks and a crown that would comfortably shade a dozen picnic tables and a toilet block. This was on John and Judy McDonald’s land, I figured. But when the dam was full I would be fifteen metres under water. Above my camp was a cliff fifty metres high. To the east, in the crook of a big sweep of the river, was a paddock of the best river-flat pasture you could wish for anywhere on Earth, and a mob of fat steers. I imagined them butchered and sizzling on barbecues in Newcastle and all down the coast. Where will your steaks come from, your milk and your cream and your yoghurt, when all this is lost? Where will that all come from in sixty years time and why don’t we think of long-term food production as well as long-term water management? But the moon was up again and my mind was wandering….

On the third day it was really obvious: far fewer weeds and more electric fences. Imagine walking up a river, pack on back and wet to the crotch, and there’s a slender wire across your path. An insulator at each end of the wire and a tickle down your stick at you gently touch…. Over or under? And the consequences, standing in water, should wire and body touch? I bet the cows learn quickly. But the cows are there, and the weeds mostly aren’t, and the water still looks clear and there are just as many water dragons and kingfishers today as on the first day, and the river banks seem to me to be holding together as well as they would have when the kangaroos and wallabies must have found their places to come down to drink.

My photographs here could just about pass for a wild river, one where you could imagine the eucalypts across the hills and flats led down to rainforest margins and giant river oaks and water gums like in Gringai times. Up here, past Tunnybuc, the McDonald’s homestead they’ll be forced to leave, the water might only come up to the kitchen bench at best, and the rest of the time the house will stand like a ghost by a strip of lake that will meander with the line of the river.

This is the saddest part, all these places, up the main river and up the side streams, that will be destroyed even though they will only be under water when the dam is full. This is the most precious part of the river. The water gums pleach overhead and I walk in a tunnel of wildness to the highest point of the reservoir’s lapping.

A little further on, just above the entry of Bullee Cuggee Creek, I clamber up the bank and out into a paddock. There’s a farmhouse up by the road and Rhonda Fisher is mowing the lawn while James milks the cows. She is startled to see this ragged and weary figure in sodden shoes. Yes their house will be above the lake, but the road will be gone and they haven’t been told where the new road will go. It’s like a sickness, for all who live in this valley, so uncertain, so stressful, so sad.

But I have my photographs. They’ll go in a museum one day, or maybe Hunter Water will set up a little Information Centre at the Dam wall with a shot or two of the way the river used to be. Twenty-two kilometres of living river, traded for the Tillegra Dam. It’s an awfully big meddle.

And an awfully big irony, because all those people up the valley get by on tank water.